Missing conversations with one old farmer in particular — my dad Vernon A. Lawrence — this Father’s Day

One part of my job I always enjoy is interviewing older farmers. They are almost all patient with my dumb questions, provide quality information and insight, and often have delightful senses of humor.

I think that’s because they got to spend their lives doing what they love. They didn’t drag out of bed in the morning and force themselves to get to the office and put in their eight hours.

For most of them, eight hours would be a light day. They spent decades putting in far longer hours, often in cold weather, or while battling rain, hail, snow or whatever combination of weather greeted them.

They did it with a smile on their face, too. Because they love the work, despite the grueling schedule, the financial pressures that are frequently out of their control, and the inherent risks of working around large machines, livestock and rampaging bankers, who often are the most dangerous.

I have been writing about agriculture for decades, and I learn more every year. At some point, I might even get good at this.

I enjoy the challenge of learning and trying to understand the complexities of modern agriculture. It’s a lot different than what I knew growing up on our farm outside Estelline in South Dakota.

Our roots go back to the 1880s, before South Dakota was a state. My grandfather Lewis Lawrence was born in a sod hut in the area in 1884. His parents, Knute Ole Lawrence and Anna Kittelsdatter Peterson, were farmers, but tragedy struck in 1887, and Anna died.

Knute soon left the farm, and my grandpa had a difficult, almost Dickensian childhood, passed from relative to relative, at times sleeping in barns. His relationship with this father, who showed up years later, was always strained, which is understandable.

Knute died in 1938. Online reports say he died in Estelline, although we were always told he wandered away after one final argument with his son, and was last seen in Portland, Ore., where he was reportedly homeless. We have no idea where he was buried.

Unlike Knute and Lewis — yes, Dad’s side of the family was Norwegian — Grandpa Lawrence and our dad, Vernon Lawrence, had a close relationship. Dad called Grandpa “Pa,” which we giggled about, since it seemed old-fashioned.

They farmed together, went to ballgames and horse races and remained close until Grandpa died, at 86 years old, in 1971. I will never forget the pain on Dad’s face when he told us his father had died.

Dad was the youngest of six kids, only three of whom survived into adulthood. He also was close to his mother, Gena — “pronounced “Gee-na” — but we know her only through family stories, since she died in 1952, when our oldest sister, Deborah, was an infant.

Grandpa, a towering, taciturn man well over 6 foot tall, was very much a presence in the life of the oldest four kids in our family. He and Dad worked together on the farm, and Dad always turned to him for advice.

Dad worked in Brookings for several years before moving back to the farm in 1966. I was just 7 and had to adjust to life in the country, as well as the sudden workload.

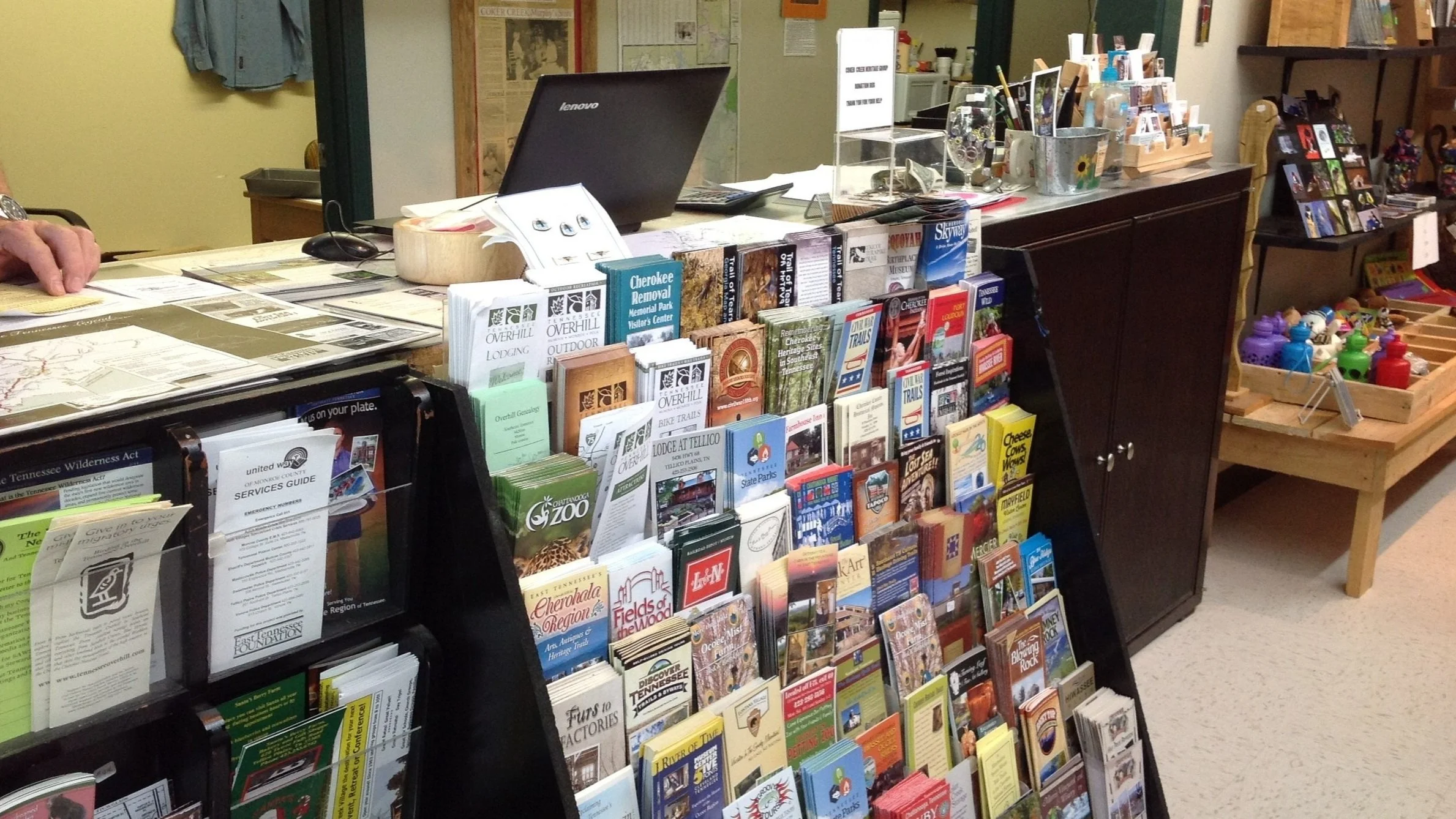

I started out feeding the chickens and collecting eggs, and as I grew older, I shifted to the barn, where I soon was the primary milker. My older brother Vern was more at home on a tractor and helped Dad (seen above in a photo provided by Tom Lawrence) with fieldwork while I fed the cows, milked them and took care of the calves.

I had an affinity for it, for some reason, and the milk production increased, and our calves grew fatter and healthier. By the time I was 16, I was offered a loan, and I bought six head of dairy cows.

I owned them for several years, buying and selling a few and raising the calves for sale. But I grew interested in newspaper work, and soon sold my cattle.

I have worked in this racket since 1978, with a few breaks, but nonstop since 1989. With a background in farming, I was usually interested in writing ag stories, and there was little competition for that beat.

Even in the Midwest, where agriculture is such a huge part of the economy, few news organizations have a farm reporter now. When I worked in Mankato, Minn., I wrote about all aspects of agriculture and enjoyed learning more about it.

When I left in 2005, a competent reporter picked up the beat, and he admitted to me he was basically clueless. I see that in newspapers and on TV stations across the region, as they either ignore ag news or do a rudimentary job of “reporting” on it, often just publishing or reciting press releases.

I had one major advantage for years — Dad. I could always call him and ask about an aspect of farming I didn’t understand. He was always willing to try to explain it to me, even if it took a while to get it through my skull.

I can’t do that anymore, since he died 11 years ago at the age of 92, taking with him countless family stories and facts and a lifetime of knowledge about cattle, chickens, corn, oats and more. Plus, he had a delightful sense of humor, never taking himself, me or life too seriously.

We rehashed my decision to choose newsrooms over barns many, many times. The work was warmer, which was a benefit. I got tired of going out on subzero days to milk, and the long, hot days in the field weren’t a lot of fun, either.

I remember Dad, however, wearing a grin as he came to the house after a 14-hour day. Like so many of the old farmers I have talked with, he loved his job. Farming for them was a lifestyle, not a career.

I still write a lot of agricultural stories, and I am constantly reminded how much I miss having him as a resource.

I guess with Father’s Day on Sunday, he has been on my mind. He’s one old farmer I would really like to hear from again.

Fourth-generation South Dakotan Tom Lawrence has written for several newspapers and websites in South Dakota and other states and contributed to The New York Times, NPR, The London Telegraph, The Daily Beast and other media outlets. Reprint with permission.