It’s OK to let it out, to cry, to face your pain. How writer/film producer Kevin Abourezk faced down his demons

Part one of a four-part series

I walked into the living room of the double-wide trailer to find an older Indian man and a younger man sitting on old, worn couches, drinking coffee and visiting while a young Lakota woman cooked breakfast. The sweet smell and crackling sound of frying bacon permeated the small room.

They laughed with each other, and I felt a weight drop inside my stomach. I couldn’t understand people who woke up like this — light, energetic, friendly. I hated them for it, and I briskly headed for the front door. The older man said with a smile, “Good morning Kevin.”

Without looking back and with frustration evident in my voice, I said, “Good morning,” and then walked out the door.

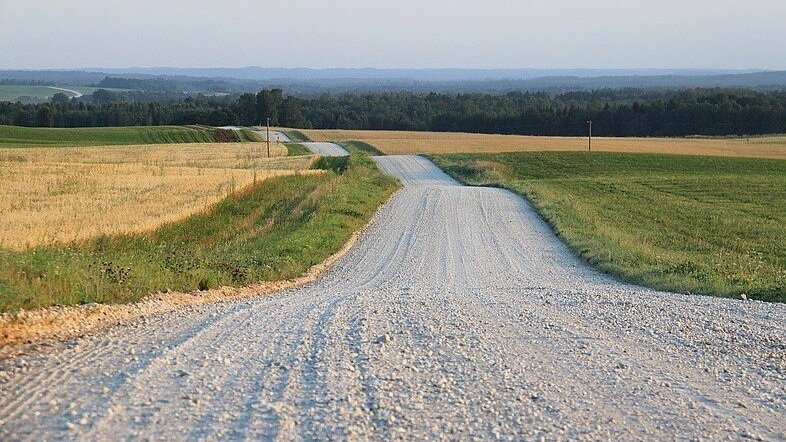

Outside, I found a frozen landscape and a light layer of snow covering the gravel of the driveway. A second double-wide sat next to the one where I and the other clients of the Sacred Winds Treatment Center slept.

I did a few stretches and then began my morning run down the country road that led west from the two buildings. To my left lay the Black Hills of South Dakota. To my right the imposing visage of Bear Butte (seen above in an 1888 photo), the sacred center of the Lakota universe.

As I ran, my breath formed small clouds in front of my face, and I thought about how much I hated being here and about the three annoying people I had just encountered. I thought about the fact that I was failing in college and might have to drop out the next semester. I thought about missing Thanksgiving with my family and friends, and then I thought about my family — my younger sister and brothers, my mom, my dad. The thought of each family member brought different feelings — warmth, love, happiness, anger and frustration.

I tried to clear my mind and think about why I was here, about the lessons I was learning — the meaning of addiction and the debilitating power of experience. I thought about the smell of burning sage, the searing heat and pounding drums inside the sacred inipi, quieting my troubled heart. Ancient memories stirred my spirit as the gravel crunched beneath my feet.

I stopped, bent over and put my hands on my knees. I thought about what my counselor had told me — that feelings aren’t bad, and must be felt in order for healing to begin. These weren’t the lessons I had learned as a child, but I fought nevertheless to trust in their truth. I stood up and looked nervously around me. The nearest building looked at least a half-mile away and there were no cars or people anywhere in sight. I looked up at the sky and began shouting, half-heartedly at first, feeling ridiculous, like a phony, a poser.

But then I heard a voice, the words of my kind, gentle counselor: It’s OK. It’s OK to cry. It’s OK to shout. Let it out. Let it go. Let go.

I began shouting louder, lifting my chin, my voice reaching to the heavens. I thought about everything, the crushing weight of failed expectations and an uncertain future bearing down on me, and I yelled and yelled. And as I did, that weight, that terrible burden, began to slowly, too slowly, dissipate.

And another feeling took its place. A deep sadness, an unabiding sorrow gripped me and drove me to the ground, and I began to cry, in a way that I hadn’t done in years, maybe ever. I began to shudder, slightly at first and then uncontrollably.

The tears came now. And I tried to let the pain wash over me, to let it flow down my shoulders, through my chest and stomach and down into my legs and feet, finally to the earth below. I fought to keep open this river of hurt, to push the banks wide with both my shaking arms and let it flow, flow.

But as I did, a voice spoke to me. “Look at you crying. Boys don’t cry.” And a face, my father’s face looking down at me, screwing his face all up and mimicking me, then blowing air through pursed lips to emulate my crying.

Inside, the banks of the river collapsed, and I fought back the tears, fought back the sorrow, and I became angry at myself for allowing such a moment of weakness to overcome me. I wiped my tears, and stood up. And then I turned around and began running back to the double-wide.

Kevin Abourezk is the deputy managing editor of Indian Country Today and an award-winning film producer who has spent his 24-year career in journalism documenting the lives, accomplishments and tragedies of Native American people. He holds a bachelor’s degree in English from the University of South Dakota and a master’s in journalism from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.